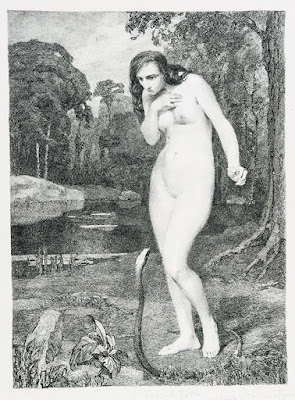

Four years later, in 1919, Decaris won the Prix de Rome for his engraving Eve before the fall, becoming the youngest ever to win this prize. He duly went to the Eternal City, where he stayed from 1920 to 1927, although his visit was interrupted for two years because of military service. From 1924 to 1926 he stayed at the Villa Médicis. When in Italy, he was known as the monk engraver, for he perfected his art by practising 15 to 16 hours a day! Although interrupted by severe illness and military service, his stay in Italy would leave an everlasting impact on Decaris, reflected in his style and his love for Greco-Roman mythology.

Back in France, Decaris soon became an enormously prolific artist; engraving, painting in water colours, every subject and theme possible. His book illustrations, for some 200 volumes published between 1928 and 1954, bring him fame. The French President Charles de Gaulle admired Decaris’ work so much that he wanted no-one but Decaris to illustrate his book ‘Le fil de l'épée’ (The edge of the sword).

In 1933, Albert Decaris became part of a team of artists put together by the Minister of PTT, Jean Mistler. He had to engrave a stamp design depicting the Cloisters of Saint-Trophime d'Arle, which he managed to do successfully thanks to the precious advice of Gaston Gandon, father of one of his team mates Pierre Gandon, and also a stamp engraver.

Decaris' work was admired so much that he was able to create more than 600 stamps for France and its former colonies. Add to this some 6000 other non-stamp engravings, some large enough to be hung on church walls, and it is no wonder that Decaris is usually regarded as France’s Master Engraver of the 20th century.

The stamps for the French territories were usually given out to competition, whereas the French stamps were normally given to those who were thought to be most specialised in the subject matter which had to be engraved. Generally speaking, the engravers were given two to three weeks for a stamp engraving.

Decaris' style is sometimes described as a mix of classicism and audacity. It is very recognisable, which is partly because, once established, he never changed his style much. As an all-round engraver, Decaris was praised for his work depicting all sorts of subjects: from architecture to landscapes, and from portraits to historical scenes.

Decaris' work was admired so much that he was able to create more than 600 stamps for France and its former colonies. Add to this some 6000 other non-stamp engravings, some large enough to be hung on church walls, and it is no wonder that Decaris is usually regarded as France’s Master Engraver of the 20th century.

The stamps for the French territories were usually given out to competition, whereas the French stamps were normally given to those who were thought to be most specialised in the subject matter which had to be engraved. Generally speaking, the engravers were given two to three weeks for a stamp engraving.

Decaris' style is sometimes described as a mix of classicism and audacity. It is very recognisable, which is partly because, once established, he never changed his style much. As an all-round engraver, Decaris was praised for his work depicting all sorts of subjects: from architecture to landscapes, and from portraits to historical scenes.

The most outstanding of the latter is undoubtedly the French series of historical scenes, which was introduced in 1966. The ‘History of France’ series would run until 1973, with every year three values being issued. The whole set depicts the complete history of France, from Vercingétorix in Roman times to the Coronation of Napoleon in 1804. Concurrently, a smaller number of similar stamp issues were engraved for Andorra.

Being such a celebrated engraver, it goes without saying that Decaris was also asked to produce his own Marianne. Unfortunately, only the one value of his Marianne de Decaris was ever issued, in 1960. The stamp was printed in letterpress which may have contributed to its early demise.

Decaris did also engrave the next Marianne definitive: the Marianne de Cocteau, It has become noteworthy, for being the first small-format definitive to be printed from the new TD-6 printing presses. This meant that Decaris had to change his original engraving, which was based on the then current, slightly smaller, stamp size for letterpress definitives. The new intaglio presses needed a taller stamp format, so Decaris had to add 1mm at bot the top and bottom of the stamp, and re-engrave the lettering on both ends. Die proofs exist of both the original smaller and eventual larger stamp engraving. It was also the first definitive to be printed from both a direct and an indirect recess cylinder.

Although only the one value was ever issued, the design was memorable and it was therefore used again in 1982, for a stamp issue promoting Philexfrance 82. The issue, two values in a miniature sheet, was only available at the show, as part of the entrance ticket one had to buy. The show's catalogue included a version of the miniature sheet printed in black only.

Decaris' passion for his art and the art of stamp engraving shines through in the following record of his thoughts: The art of engraving requires dedication, patience, precision, tenacity and concentration, as has been the case for centuries. In a world which sees an increase of instant-made objects, it is the engraver who is safeguarding the survival of slow and minute work. The postage stamp is to thank for making it possible for the art of engraving to survive and the stamp albums of our collectors show the world that art is eternal, that it answers the cry of the human soul, and that it is a law on its own, not answering to anything or anyone.

In 1955, when the first of a small series of booklets named 'Ceux qui créent nos timbres' (they who create our stamps) was published. Decaris not only wrote the introduction, and was featured in it as well, but also submitted a large engraving of the goddess Ceres.

Being such a celebrated engraver, it goes without saying that Decaris was also asked to produce his own Marianne. Unfortunately, only the one value of his Marianne de Decaris was ever issued, in 1960. The stamp was printed in letterpress which may have contributed to its early demise.

Decaris’ own non-Marianne definitive fared much better. It was his Gallic Cock design and engraving, introduced in 1962. Although only two values were ever made, it has become quite an iconic stamp in France’s catalogue.

Decaris did also engrave the next Marianne definitive: the Marianne de Cocteau, It has become noteworthy, for being the first small-format definitive to be printed from the new TD-6 printing presses. This meant that Decaris had to change his original engraving, which was based on the then current, slightly smaller, stamp size for letterpress definitives. The new intaglio presses needed a taller stamp format, so Decaris had to add 1mm at bot the top and bottom of the stamp, and re-engrave the lettering on both ends. Die proofs exist of both the original smaller and eventual larger stamp engraving. It was also the first definitive to be printed from both a direct and an indirect recess cylinder.

Although only the one value was ever issued, the design was memorable and it was therefore used again in 1982, for a stamp issue promoting Philexfrance 82. The issue, two values in a miniature sheet, was only available at the show, as part of the entrance ticket one had to buy. The show's catalogue included a version of the miniature sheet printed in black only.

Decaris' passion for his art and the art of stamp engraving shines through in the following record of his thoughts: The art of engraving requires dedication, patience, precision, tenacity and concentration, as has been the case for centuries. In a world which sees an increase of instant-made objects, it is the engraver who is safeguarding the survival of slow and minute work. The postage stamp is to thank for making it possible for the art of engraving to survive and the stamp albums of our collectors show the world that art is eternal, that it answers the cry of the human soul, and that it is a law on its own, not answering to anything or anyone.

In 1955, when the first of a small series of booklets named 'Ceux qui créent nos timbres' (they who create our stamps) was published. Decaris not only wrote the introduction, and was featured in it as well, but also submitted a large engraving of the goddess Ceres.

Decaris was also an influential figure for the next generations of stamp engravers. When René Quillivic won the Prix de Rome in 1950, he did not go to Rome but instead accepted an invitation by Decaris to join him at the Casa de Velazquez in Madrid, Spain. Decaris, having seen Quillivic's work, considered Rome to be too classical an influence on Quillivic and figured a more modern environment would be more conducive to Quillivic's development as an artist.

During his long career, Decaris often received honours for his work. In 1943 he was elected a fellow of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, and he would later become its president. Decaris also received the Légion d’Honneur medal, and was even proclaimed official ‘naval painter’. In 1981, a large exposition in the French Postal Museum honoured his work done for the postal authorities.

Albert Decaris' final stamp issue was the 1985 French stamp marking National Memorial Day. He passed away in Paris, on 1 January 1988. Most fittingly, a stamp was issued in 2001 stamp issue to mark the birth centenary of Decaris. Designed and engraved by Claude Jumelet, the design pays homage to Decaris’ more humorous side, by depicting the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe dancing together. It is no coincidence that it looks very much in the Decaris style, because it is more or less based on one of his final engravings, to mark the centenary of the Eiffel Tower in 1989.

Albert Decaris' final stamp issue was the 1985 French stamp marking National Memorial Day. He passed away in Paris, on 1 January 1988. Most fittingly, a stamp was issued in 2001 stamp issue to mark the birth centenary of Decaris. Designed and engraved by Claude Jumelet, the design pays homage to Decaris’ more humorous side, by depicting the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe dancing together. It is no coincidence that it looks very much in the Decaris style, because it is more or less based on one of his final engravings, to mark the centenary of the Eiffel Tower in 1989.

You will find Albert Decaris' database HERE.