Ferdinand Schirnböck is synonymous with the engraved

stamps of Austria. In an era dominated by letterpress printing, he visualised

the final years of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in intaglio, and went on to

produce many of the early issues of its successor republic.

But Schirnböck’s output encompassed 14 other

countries too, and indeed his career started on the other side of the world.

Born in Hollabrunn, north of Vienna, on 27 August 1859,

Schirnböck trained at the Vienna Academy’s school for engravers, after having been a couple of years at the Vienna

Professional School, where F. Laufberger was his teacher. When he

graduated at the age of 27, his first full-time job took him all the way to

Argentina, where he joined the South American Bank Note Company in Buenos

Aires.

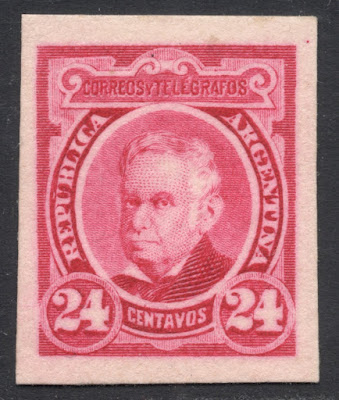

In his five years there, from 1887-92, he engraved

most of the stamps issued by Argentina, notably an array of definitives

portraying historic figures.

Schirnböck started by engraving all values of the

definitive sets issued in 1888 to 1892. He also engraved a good number of

stamps which made it to the colour proof stage but were eventually not issued.

Of those, the actual portrait was sometimes used but then with another frame

for a different value.

Besides the issued stamp portraits, of which many proofs may be found, there are a good number of die essays of unaccepted portraits on the market as well. With these stamps, and with his engravings of banknotes as well, Schirnböck managed to build quite a reputation for himself because of the quality of his work. This probably resulted in him being asked to engrave a series of portraits of national dignitaries.

In 1893, a special engraving made for an SABNC exhibit at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, United States, led to Schirnböck receiving a ‘Diploma of Honorable Mention’ in 1895.

There is uncertainty regarding Schirnböck’s final engravings. Until recently, there were only anecdotal sources crediting the 1892 Argentine set marking the fourth centenary of the discovery of America by Columbus to Schirnböck. However, a competitive display held in the 1990s included a progressive die proof of this engraving which came from the estate of the engraver Nuesch. The philatelist Walter Rose, in his 1968 book La emisión conmemorativa del IVº Centenario del Descubrimiento de América 1892 also mentions Nuesch as the engraver of this issue. It is said that Rose had access to archives and printing proofs. It seemed therefore that the more reliable evidence points towards Nuesch having been the engraver. The stamps were only issued in late October 1892, so the fact that Schirnböck left the SABNC and Argentina in early 1892 and Nuesch succeeded him as master engraver at the company would also make Nuesch the more likely candidate.

However, in Walter Sendlhofer’s book on Schirnböck, published in 2018, a letter is quoted from the General Secretary of the Argentine Post, in which Schirnböck is mentioned and hailed as the artist responsible for this issue. This seems to be quite convincing evidence that the stamps were after all engraved by Schirnböck.

Besides the issued stamp portraits, of which many proofs may be found, there are a good number of die essays of unaccepted portraits on the market as well. With these stamps, and with his engravings of banknotes as well, Schirnböck managed to build quite a reputation for himself because of the quality of his work. This probably resulted in him being asked to engrave a series of portraits of national dignitaries.

In 1893, a special engraving made for an SABNC exhibit at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, United States, led to Schirnböck receiving a ‘Diploma of Honorable Mention’ in 1895.

There is uncertainty regarding Schirnböck’s final engravings. Until recently, there were only anecdotal sources crediting the 1892 Argentine set marking the fourth centenary of the discovery of America by Columbus to Schirnböck. However, a competitive display held in the 1990s included a progressive die proof of this engraving which came from the estate of the engraver Nuesch. The philatelist Walter Rose, in his 1968 book La emisión conmemorativa del IVº Centenario del Descubrimiento de América 1892 also mentions Nuesch as the engraver of this issue. It is said that Rose had access to archives and printing proofs. It seemed therefore that the more reliable evidence points towards Nuesch having been the engraver. The stamps were only issued in late October 1892, so the fact that Schirnböck left the SABNC and Argentina in early 1892 and Nuesch succeeded him as master engraver at the company would also make Nuesch the more likely candidate.

However, in Walter Sendlhofer’s book on Schirnböck, published in 2018, a letter is quoted from the General Secretary of the Argentine Post, in which Schirnböck is mentioned and hailed as the artist responsible for this issue. This seems to be quite convincing evidence that the stamps were after all engraved by Schirnböck.

The stamps were only on sale for one day, after

which the master die was defaced with vertical lines. However, that didn’t stop

the authorities from pulling some more proofs from the die.

Next Schirnböck moved to Portugal, where he spent

1893 engraving banknotes in Lisbon. Only in 1894 did he return to his homeland.

His major breakthrough in Austria came two years

later when he was given an important imperial commission, to produce a copper

engraving of Franz Defregger’s painting Delivery

of Imperialistic Gifts to Andreas Hofer in the Palace at Innsbruck,

honouring a national hero of the Tyrol region. This

copper engraving was subsidised by the Emperor Franz Joseph, a staunch patron

of the arts.

The work was well received, and further commissions

followed. Most importantly, Schirnböck was given a contract with the

Staatsdruckerei, the government printing office, of which he would become the

master engraver.

In his first decade there, he mostly engraved

banknotes. But in 1906 he collaborated with the renowned designer Koloman Moser

to produce a 16-value stamp issue for Bosnia & Herzegovina, a province of

the Ottoman Empire which was under long-term Austrian occupation and would soon

be annexed.

The issue set a high standard for what was then

still a novelty in stamp design: scenic illustrations. It won worldwide

admiration, cementing Schirnböck’s reputation and inaugurating a successful

partnership with Moser, the doyen of Vienna’s groundbreaking Secessionist art

movement.

It also earned the pair the chance to create

Austria’s first commemorative issue: a set of 18 stamps (of which seven were

engraved) issued in 1908 to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the accession of

the Emperor Franz Josef. Moser and Schirnböck produced a mixture of royal

portraits and scenic views which were both imperial and imposing. Some of the values were also made available, with minor

tweaks, to the Austrian post offices in the Turkish Empire.

The stamp issue was accompanied by a special Jubilee postcard. Although usually contributed to Schirnböck, Sendlhofer’s book argues that he only engraved the frame, and that both the portrait and the vignettes were engraved by William Unger. However, die proofs exist which were only signed by Moser as the designer and Schirnböck as the engraver. Two versions of the card exist; the regular one with Austrian views in the side panels, and a second one with Prague views.

The stamp issue was accompanied by a special Jubilee postcard. Although usually contributed to Schirnböck, Sendlhofer’s book argues that he only engraved the frame, and that both the portrait and the vignettes were engraved by William Unger. However, die proofs exist which were only signed by Moser as the designer and Schirnböck as the engraver. Two versions of the card exist; the regular one with Austrian views in the side panels, and a second one with Prague views.

The stamp set would be

reissued in 1910 with extra panels added, this time marking the emperor’s

eightieth birthday. The same procedure was followed in Bosnia & Herzegovina,

where the 1906 set was reissued with extra commemorative panels added to the

designs.

In 1911, Schirnböck engraved a non-postal label for

the International Stamp Exhibition held in Vienna that year. Like many of the

stamp issues mentioned before, this label, which was printed in at least ten

different colours, was also the result of Schirnböck’s collaboration with his

sidekick designer Koloman Moser.

In 1912, three more values would be added to the original 1906 Bosnia & Herzegovina set, with new scenes engraved. That year would also see a new definitive set issued for Bosnia & Herzegovina. This set included two different portraits of Franz Joseph. With the kronen values being larger, Schirnböck had to engrave four different dies for this set. A similar set followed in 1916, but this time only two dies were required.

In 1912, three more values would be added to the original 1906 Bosnia & Herzegovina set, with new scenes engraved. That year would also see a new definitive set issued for Bosnia & Herzegovina. This set included two different portraits of Franz Joseph. With the kronen values being larger, Schirnböck had to engrave four different dies for this set. A similar set followed in 1916, but this time only two dies were required.

Schirnböck also engraved many issues for other

countries, including Montenegro’s 1907 definitives, Siam’s 1912 definitives and

Norway’s 1914 commemorative issue marking the centenary of its independence. Also in 1914, Schirnböck engraved a definitive design for

Luxembourg, portraying the Grand Duchess Marie Adelaide. Although many

Turkish issues during World War I are still unaccounted for, Sendlhofer’s book

attributes the 1916 definitive set to Schirnböck, as well as the 1917 War

Charity stamp and the 1917 ‘In the trenches’ stamp, which was only issued with

an overprinted surcharge.

During World War I, though, it was Schirnböck’s work

which dominated the last stamps of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He engraved the

high-value definitives of 1916 and all the issues of the military field post,

bearing portraits of the Emperor Franz Josef and his successor Karl I, some of

which were adapted to be used in Romania, Italy, Serbia and Montenegro, though

the latter three only as overprinted versions of either general or Romanian

stamps, as the empire fought its final battles before disintegrating in 1918.

Schirnböck’s favourite design partner, Moser, died

at around the same time, but Schirnböck survived to produce many more

beautifully engraved sets for Austria, in its considerably reduced state as a

republic.

Forming a new partnership with the designer Rudolf

Junk, which proved just as fruitful, he produced what many consider his finest

work in the post-war period. This included the 1922 Musicians’ Fund set of

seven, portraying Mozart, Beethoven and other classical composers, and the even

more stunning 1923 Artists’ Charity Fund set of nine, illustrating Austrian

views.

Also in 1923, he would create a beautifully executed

pictorial definitive for Luxembourg, showing a scene near Echternach.

Schirnböck became partly responsible, too, for

teaching the next generation of stamp engravers, most

noticeably the Swedish engraver Sven Ewert, from 1906 to 1916. Ewert would, in

his turn, go on and dominate the Swedish stamp scene for many decades.

Schirnböck's influence in Scandinavian matters remained strong after that, for he also taught the Polish engraver Marian Polak who, in his turn, taught everything he had learnt from Schirnböck to his pupil Czeslaw Slania, the engraver who would dominate the Scandinavian stamp scene (and indeed that of the whole world) as Ewert's successor.

It had been Schirnböck's worldwide reputation as a master engraver which initiated these Swedish links. When a new king, Gustav V, acceded the Swedish throne in 1907, and work on a new definitive set had started, three engravers were asked to submit a die essay of the new design, among which Schirnböck. His work was deemed most suitable, so Schirnböck got commissioned to engrave the actual stamp, which was introduced in 1911 and would remain in circulation for a whole decade.

The famous engraver Professor Alfred Cossmann, who had a school training future Austrian stamp engravers, sometimes sent his pupils to Schirnböck, when he thought their way of working would suit Schirnböck better. Among those were the likes of Rupert Franke and RudolphZenziger, whose names appear in the Austrian catalogues after World War Two.

Schirnböck's influence in Scandinavian matters remained strong after that, for he also taught the Polish engraver Marian Polak who, in his turn, taught everything he had learnt from Schirnböck to his pupil Czeslaw Slania, the engraver who would dominate the Scandinavian stamp scene (and indeed that of the whole world) as Ewert's successor.

It had been Schirnböck's worldwide reputation as a master engraver which initiated these Swedish links. When a new king, Gustav V, acceded the Swedish throne in 1907, and work on a new definitive set had started, three engravers were asked to submit a die essay of the new design, among which Schirnböck. His work was deemed most suitable, so Schirnböck got commissioned to engrave the actual stamp, which was introduced in 1911 and would remain in circulation for a whole decade.

The famous engraver Professor Alfred Cossmann, who had a school training future Austrian stamp engravers, sometimes sent his pupils to Schirnböck, when he thought their way of working would suit Schirnböck better. Among those were the likes of Rupert Franke and RudolphZenziger, whose names appear in the Austrian catalogues after World War Two.

Much later, Schirnböck would also set the wheels in

motion to train another now famous stamp engraver, Bohumil Heinz, but

unfortunately, Schirnböck passed away before this could come to fruition.

Schirnböck made his final engraving for Austria in

1930, a portrait of President Wilhelm Miklas for the Anti-Tuberculosis Fund

set.

He died later that year, at

his home in Perchtoldsdorf, a suburb of Vienna, where he had a studio, on 16

September, while working on a definitive set for Vatican City, which

would eventually be issued in 1933. A fellow engraver

in Rome, Enrico Federici, is therefore also responsible for quite a bit of work on

this set. The question is who did what?

There are six designs in this set. The vignettes of two of those, featuring a Wing of the Vatican Palace (10c to 25 c values) and the Vatican Gardens (30c to 80c values) are most certainly by Schirnböck seeing that they include his initials. On the Palace value they may be found just to the left of the circle bearing the denomination and on the Gardens vignette they may be found in the right-hand bottom. Whilst some ascertain that Schirnböck engraved all vignettes, and Federici ‘merely’ the 5c value and all frames, others have stated that the style of engraving of particularly the backgrounds on the all lire values are not much like Schirnböck’s. Nowadays, catalogues therefore state that the 5c and all lire values will have been engraved by Federici.

As for the accompanying express letter stamps, the vignette of those include Schirnböck’s full name, whereas it is thought the frame will have been done by Federici.

There are six designs in this set. The vignettes of two of those, featuring a Wing of the Vatican Palace (10c to 25 c values) and the Vatican Gardens (30c to 80c values) are most certainly by Schirnböck seeing that they include his initials. On the Palace value they may be found just to the left of the circle bearing the denomination and on the Gardens vignette they may be found in the right-hand bottom. Whilst some ascertain that Schirnböck engraved all vignettes, and Federici ‘merely’ the 5c value and all frames, others have stated that the style of engraving of particularly the backgrounds on the all lire values are not much like Schirnböck’s. Nowadays, catalogues therefore state that the 5c and all lire values will have been engraved by Federici.

As for the accompanying express letter stamps, the vignette of those include Schirnböck’s full name, whereas it is thought the frame will have been done by Federici.

Incredibly, Schirnböck had managed to keep working

to a high level right up to his death, despite having lost his sight in one

eye!

You will find Ferdinand Schirnböck's database HERE.

You will find Ferdinand Schirnböck's database HERE.