Karl Bickel was born on 13 February 1886, in

Zürich-Hirslanden, Switzerland. He lost his father when he was only four and

was then raised mainly by his mother, even though she did remarry after a

while. Karl enjoyed a free upbringing and spent his time dreaming of various

careers, ranging from entering a monastery to something to do with machines,

and everything in between.

It was quite a coincidence that he entered the lithography

business. After having applied for various apprenticeships in 1900, Paul

Bleuler’s well-known graphic art company was the first to react, offering him a

position to learn the art of lithography. Karl Bickel stayed for four years

during which time he occupied himself mainly with designing and drawing picture

postcards.

After his apprenticeship, Bickel was employed by the graphic

art company Hüttner where he soon made it to technical head. Again, Bickel

created picture postcards, but also fashion and other catalogues.

Every year, though, he would take three months off to work

on his artistic talents. He followed courses in graphic art and drawing. In

this period, his love for nature and romantic landscapes was taking shape. His

first art exhibition took place in 1909.

By that time, Bickel had just opened his own studio,

together with some employees he had worked with at Hüttner’s. They designed and

produced letter heads, business cards and fashion catalogues. Bickel was the

one who created the whole design and subsequently focused on the drawing of any

portraits in it. His colleagues were then employed to finish the design as they

saw fit. From 1912, however, Karl Bickel’s fierce sense of independence induced

him to leave his colleagues behind and go his own way.

That year, he was invited to a study trip to Italy. There he

came under the spell of Michelangelo’s sculptures; the demonic force which

Michelangelo must have used to create his masterworks. It proved to be a

pivotal moment for the young Swiss, who up to now had only been influenced by

art books. When he arrived at Carrara, Bickel took up sculpting marble himself,

until a message from home forced him to end his trip prematurely and return to

Switzerland.

A second pivotal moment in Bickel’s life took place in

February 1913, when he contracted tuberculosis. He spent the next 13 months in

a sanatorium in Walenstadtberg, having initially almost been given up by his

doctors. It was a deeply introspective period for Bickel, immediately followed

by the outbreak of World War One. Bickel created his vision of a community of

labour, justice and peace and vowed that if he would manage to beat his

illness, he would devote his life to his vision. All his future work would in

one way or another be connected to it.

Back

home, Bickel became more and more involved in poster art, while he also

specialised in figurative art. As an autodidact, he studied medical literature

to thoroughly acquaint himself with every aspect of the human body. He

translated this knowledge into recess art such as copper engraving, diamond

engraving, drypoint and etching.

Bickel

spent more and more time in the Walenstadtberg area, where he had recuperated

from his illness. There he tried to capture the grandeur of the mountains, the

rocks, the magnificent trees. He saw the rocks as monuments of nature, shaped

by the force of the earth.

In the 1920s, after his mother had died, Karl Bickel had

enough of city life and retired to the mountains above Walenstadtberg. There he

started building what was to become his life’s work: the Pax Mal monument; a

temple of peace high up in the mountains.

Thanks to the mediation of printing firm Wolfensberger, Karl

Bickel received his first commission from the Swiss PTT in Bern. He produced a

copper engraving of René de St. Marceaux’s UPU monument, to mark the

50th anniversary of the Universal Postal Union. Bickel had always had an

interest in stamps and is quoted as having said that the superiority of the

British Penny Black and the old Victorian stamps from the British Commonwealth

inspired him to try and improve the inferior Swiss stamps of those days.

It would form the start of a long-lasting relationship between

Bickel and the Swiss Post. However, initially, Bickel’s work was ‘limited’ to

design rather than engraving. During his first years working for the Swiss PTT

he designed banknotes and various airmail stamps. He would divide his time in

two; six month’s a year he would work on his mountain monument, the other six

he would devote to designing and later also engraving postage stamps.

Bickel’s early days at the PTT were far from smooth,

however. His first stamp designs, for the 1923 Airmail set, were not received

favourably. Too bold and too modern were criticisms often heard. Thankfully,

the authorities at the Swiss PTT had enough faith in Karl Bickel not to release

him from his duties.

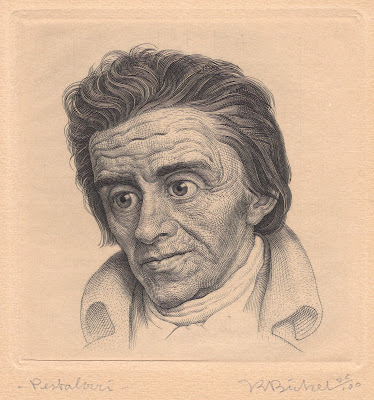

Bickel’s

breakthrough came in 1927. The children’s charity Pro Juventute wanted to mark

the death centenary of the Swiss educational reformer Heinrich Pestalozzi. It

would be the first time the annual Pro Juventute stamps would include a

portrait stamp.

The logical choice was to ask Bickel for this stamp. He had

been deeply impressed by Pestalozzi’s ideas of life being subdivided in various

spheres; from family via self-determination to inner sense, which, if guided by

good education, would lead to inner peace. These were ideas Bickel himself

tried to give shape in his mountain monument. In fact, Pestalozzi is

represented in one of the mosaics in the monument, and he would also be a

returning figure in Bickels’ stamp engravings.

Bickel's first engraved stamp is one of the very few of which colour proofs are available on the open market. They come in four colours: black, green, pink and purple.

In 1946, Bickel was asked to engrave his second Swiss stamp portraying Heinrich Pestalozzi. This commemorative stamp marked the bicentenary of Pestalozzi’s birth. The stamp design was based on a 19th century bas-relief. As part of the PTT’s promotional material, Bickel engraved yet another portrait of Pestalozzi, which very much resembled his work done for the 1927 Pro Juventute stamp.

Bickel's first engraved stamp is one of the very few of which colour proofs are available on the open market. They come in four colours: black, green, pink and purple.

In 1946, Bickel was asked to engrave his second Swiss stamp portraying Heinrich Pestalozzi. This commemorative stamp marked the bicentenary of Pestalozzi’s birth. The stamp design was based on a 19th century bas-relief. As part of the PTT’s promotional material, Bickel engraved yet another portrait of Pestalozzi, which very much resembled his work done for the 1927 Pro Juventute stamp.

With his engraving of his first stamp, this moving portrait

of Pestalozzi, Bickel proved that he was no mere copier of existing art, be it

old engravings, paintings or photographs. He was able to pinpoint the

essence of an image and transport it to his own work. It would remain one of

his favourite stamps.

Karl

Bickel’s next engravings would not be issued until 1932. That year, the

fiftieth anniversary of the opening of the St Gotthard railway line was

celebrated with a set of three stamps, portraying three men pivotal to that

immense railway project.

As part of the festivities, the Swiss PTT produced a limited quantity of

souvenir booklets which included mint and cancelled blocks of the St Gotthard

stamps. The booklets also included three single die proofs of the three stamp

engravings. Only 800 of these booklets have been made. They were distributed

among officials and highly ranked guests participating in the festivities.

The St Gotthard portraits were so beautifully engraved that it landed Karl Bickel the enviable task of engraving all subsequent portraits for the annual Pro Juventute series, which he did until his final portrait of 1964. The series of portraits Bickel engraved for this series are among the finest in philately; they are not mere portraits but miniature studies of character.

Bickel’s obviously huge engraving talents also made him first choice when the Swiss PTT decided to replace its unpopular landscape definitives, issued in 1934 and printed by letterpress, with a similar set but printed in recess. In 1935, they had bought a new printing press to be able to print these new stamps in recess: the SSR I made by Goebel in Germany. Karl Bickel engraved the trial stamps, in the Cross and Wavy Lines design, which were used to test run this new press.

The St Gotthard portraits were so beautifully engraved that it landed Karl Bickel the enviable task of engraving all subsequent portraits for the annual Pro Juventute series, which he did until his final portrait of 1964. The series of portraits Bickel engraved for this series are among the finest in philately; they are not mere portraits but miniature studies of character.

Bickel’s obviously huge engraving talents also made him first choice when the Swiss PTT decided to replace its unpopular landscape definitives, issued in 1934 and printed by letterpress, with a similar set but printed in recess. In 1935, they had bought a new printing press to be able to print these new stamps in recess: the SSR I made by Goebel in Germany. Karl Bickel engraved the trial stamps, in the Cross and Wavy Lines design, which were used to test run this new press.

Bickel’s admiration for the Swiss mountains made him the

best candidate for the job of creating the new definitives. In fact, rather

than just copying the existing stamps, Bickel went on a bicycle trip in 1935

and visited all the sights depicted on the stamps, made elaborate sketches and

worked from these, rather than the stamp designs. His engravings were an

instant hit among the Swiss when they appeared in 1936. The seven values up to

30c were loosely based on the existing stamps, but the two highest values, the

35c and 40c, were new designs by Bickel.

The definitives depict various scenes showing off the variety in the Swiss landscape. The 3 cents olive shows the Staubbach Falls in the Lauterbrunnen Valley. The Falls plunge more than 300 metres into the valley which is enclosed by high rock faces. By avoiding too much stylisation, and making a smooth engraving, Bickel managed to avoid hard lines, thereby lessening the impact of the massive rocks and stressing the charm of this mountain valley.

The die proofs show how Bickel tried to find the perfect placement, space and depth by experimenting with the foreground and the skyline. In order not to focus the eye too much on the foreground, the village has just merely been hinted at. The bottom part of the waterfall has been engraved in such a way that it is clear we’re dealing with a wild waterfall here. Bickel managed to include many details despite the small size of the stamp.

The definitives depict various scenes showing off the variety in the Swiss landscape. The 3 cents olive shows the Staubbach Falls in the Lauterbrunnen Valley. The Falls plunge more than 300 metres into the valley which is enclosed by high rock faces. By avoiding too much stylisation, and making a smooth engraving, Bickel managed to avoid hard lines, thereby lessening the impact of the massive rocks and stressing the charm of this mountain valley.

The die proofs show how Bickel tried to find the perfect placement, space and depth by experimenting with the foreground and the skyline. In order not to focus the eye too much on the foreground, the village has just merely been hinted at. The bottom part of the waterfall has been engraved in such a way that it is clear we’re dealing with a wild waterfall here. Bickel managed to include many details despite the small size of the stamp.

The

5 cents green depicts Mt. Pilatus at Lake Lucerne, a wild and rugged mountain

group. The image shows the village of Stansstad in the foreground, situated on

Hergiswil Bay. By engraving the mountain rather forcefully and sharply, Bickel

accentuated the wildness of the peaks and ridges of the mountain. Another fine

detail in the engraving is that of the variety of trees near the tower. By

setting these off against the mere hint of trees on the foot hills of Mt.

Pilatus, Bickel managed to create enormous depth in his engraving. Note also

the peculiar cloud formations around the peaks; these are a specific weather

pattern for the mountain.

The die proofs show that Bickel used this value to work out where to place the country name and the denomination. While first experimenting with how they were placed on their letterpress predecessors, Bickel eventually settled for having both in one line at the bottom of the stamp. This is where they would be for all values from this series.

The 10 cents violet shows one of the best known views in Switzerland: Chillon Castle on Lake Geneva with the Dents du Midi in the background. The die proofs show that Bickel experimented with light and shadow on this stamp. He first placed the whole scene in evening sunshine, but that yielded too many light areas on both the castle and the mountains. In order to achieve a more evenly toned stamp, he changed the time to morning, when both castle and mountain would be seen shaded. Further work on the original die consisted mainly of leaving out cluttering details such as sailing ships and various railway details.

The die proofs show that Bickel used this value to work out where to place the country name and the denomination. While first experimenting with how they were placed on their letterpress predecessors, Bickel eventually settled for having both in one line at the bottom of the stamp. This is where they would be for all values from this series.

The 10 cents violet shows one of the best known views in Switzerland: Chillon Castle on Lake Geneva with the Dents du Midi in the background. The die proofs show that Bickel experimented with light and shadow on this stamp. He first placed the whole scene in evening sunshine, but that yielded too many light areas on both the castle and the mountains. In order to achieve a more evenly toned stamp, he changed the time to morning, when both castle and mountain would be seen shaded. Further work on the original die consisted mainly of leaving out cluttering details such as sailing ships and various railway details.

The

15 cents orange showed the Rhone Glacier. Orange is one of the most difficult

colours to print, which is why Bickel had to make a very deep engraving for

this particular value. Again, he experimented with dark and light skies, to

achieve optimal colour saturation. The inclusion or omitting of details was

also a problem to solve. Bickel removed almost all traces of the famous Grimsel

Pass road, but left just enough to show it is a road with many bends and

fabulous engineering structures. The beauty of this engraving is that Bickel

managed to depict the glacier in such a way that it is clear this is a solid

ice formation rather than a river torrent.

The 20 cents red shows the Gotthard railway in the Valle Leventina. It was one

of the hardest subjects to engrave, seeing that there is so much going on. With

the focus being very much on the road and railway, Bickel tried to emphasise

these by engraving them with much detail. In contrast, Bickel left out most

detail of the surrounding landscape. Nevertheless, this would be the stamp

which was least liked by the Swiss public, which would lead to its early

demise.

The 25 cents brown depicts one of the many gorges of Switzerland, Viamala. The gorge is incredibly narrow and offers no through view, which made it hard to translate to stamp format. Again, the imposing atmosphere is recreated through a forceful engraving, while the two fir trees, brought down by storms, add yet another dimension to the wildness of these gorges.

The 25 cents brown depicts one of the many gorges of Switzerland, Viamala. The gorge is incredibly narrow and offers no through view, which made it hard to translate to stamp format. Again, the imposing atmosphere is recreated through a forceful engraving, while the two fir trees, brought down by storms, add yet another dimension to the wildness of these gorges.

The 30 cents blue, with the Rhine Falls near Neuhausen as its subject, is proof

that subjects like these on small stamps really should be engraved for in no

other way could the wildness of the water be better represented.

The 35 cents yellow-green was one of the two new extra values added to the set. Its subject is one of the typical deep valleys of the Jura. The challenge here was to transform the many strange shapes and forms of the mountains into a convincing engraving. While Bickel initially chose to depict one of the steep valleys, he later changed his mind and went for the flat-top mountains, again typical for the Jura, while the deep engraving of distinct outlines symbolise the peculiarities of the mountain rocks. The ruin adds a romantic touch and the inclusion of a hint of a narrow pass through the mountains, realised through a wonderful play of light and shade, adds depth and scale to the whole design.

Finally, the 40 cents grey shows Lake Seealp and Mt Säntis. It is one of those many small mountain lakes in Switzerland which look tiny because of the massive mountains, yet are delightfully charming. Bickel tried to retain this delightfulness by making a fine and even engraving, and by skilfully avoiding the emphasis on individual parts of the landscape.

The 35 cents yellow-green was one of the two new extra values added to the set. Its subject is one of the typical deep valleys of the Jura. The challenge here was to transform the many strange shapes and forms of the mountains into a convincing engraving. While Bickel initially chose to depict one of the steep valleys, he later changed his mind and went for the flat-top mountains, again typical for the Jura, while the deep engraving of distinct outlines symbolise the peculiarities of the mountain rocks. The ruin adds a romantic touch and the inclusion of a hint of a narrow pass through the mountains, realised through a wonderful play of light and shade, adds depth and scale to the whole design.

Finally, the 40 cents grey shows Lake Seealp and Mt Säntis. It is one of those many small mountain lakes in Switzerland which look tiny because of the massive mountains, yet are delightfully charming. Bickel tried to retain this delightfulness by making a fine and even engraving, and by skilfully avoiding the emphasis on individual parts of the landscape.

The original 10 cents value from the Swiss Landscapes definitive set, depicting

Chillon Castle, was engraved a bit too finely. It had already been retouched in

1938 but in 1939, when it would be reissued in a new red-brown colour, a

completely new die was engraved. Not only was the engraving itself a little

coarser, to eliminate the many halftones of the original engraving, but the

placement of the various parts was also changed. The castle was moved to the

foreground by making it a bit bigger and the Dents du Midi were moved to the

background by making them a bit smaller. They were also removed from the

stamp’s top edge, which resulted in a much better balanced design.

When a new printing cylinder was needed for the 20 cents value of the Swiss Landscapes set, it was decided to create a whole new stamp, because the Swiss public were not impressed with the existing design of the Gotthard railway. The new 20 cents value would depict Mt San Salvatore and Lake Lugano. Bickel tried various views of Lake Lugano before settling on the eventual image which included the Castagnola Church.

A competition was held for designs for the three highest values of the Swiss definitive series. Eight artists took part, among whom Karl Bickel, who won the first prize for his designs. Bickel’s frame-filling figures needed a perfect play with light and shade to make them come out well. On the Swearing of the Oath scene on the 3 francs, an invisible light on the table creates a feeling of depth in the design. The 5 francs, too, depends on light and shade to make all the figures stand out. The engraving of the 10 francs is remarkable in that Bickel succeeded in portraying a vast array of figures, all from different social backgrounds, with different occupations and different status in life. The three stamps were issued in 1938.

When a new printing cylinder was needed for the 20 cents value of the Swiss Landscapes set, it was decided to create a whole new stamp, because the Swiss public were not impressed with the existing design of the Gotthard railway. The new 20 cents value would depict Mt San Salvatore and Lake Lugano. Bickel tried various views of Lake Lugano before settling on the eventual image which included the Castagnola Church.

A competition was held for designs for the three highest values of the Swiss definitive series. Eight artists took part, among whom Karl Bickel, who won the first prize for his designs. Bickel’s frame-filling figures needed a perfect play with light and shade to make them come out well. On the Swearing of the Oath scene on the 3 francs, an invisible light on the table creates a feeling of depth in the design. The 5 francs, too, depends on light and shade to make all the figures stand out. The engraving of the 10 francs is remarkable in that Bickel succeeded in portraying a vast array of figures, all from different social backgrounds, with different occupations and different status in life. The three stamps were issued in 1938.

When the decision was made to replace the existing middle

values up to 1 frank with new designs, various artists tried to come up with

new and more modern symbols to represent the country. This turned out to be

harder than originally thought. When nothing suitable surfaced, it was decided

to use imagery from old Swiss paintings. Seeing that the Swiss borders had to

be heavily armed at the time, it was soon decided to use military imagery as

well.

Bickel was asked to submit various engraved designs for

values from 50 to 90 cents. When these proved suitable, a second round of

essays followed. The initial essays had shown that a) a larger stamp size was

needed for this type of images, and b) the imagery would work better on

coloured paper, but this would need a deeper engraving to make it stand out

better.

During a second round of engraved essays, various designs were experimented with for the 50 cents value, until it was finally decided to opt for the ‘Oath Scene’, which would be a symbolic start of the remainder of the set, which were to show soldiers fighting for the union. We subsequently have William Tell on the 60 cents, a fighting soldier on the 70 cents and a dying soldier on the 80 cents. The standard bearer on the 90 cents was chosen as the perfect changeover from battlefield images to the more refined portraits of military leaders.

During a second round of engraved essays, various designs were experimented with for the 50 cents value, until it was finally decided to opt for the ‘Oath Scene’, which would be a symbolic start of the remainder of the set, which were to show soldiers fighting for the union. We subsequently have William Tell on the 60 cents, a fighting soldier on the 70 cents and a dying soldier on the 80 cents. The standard bearer on the 90 cents was chosen as the perfect changeover from battlefield images to the more refined portraits of military leaders.

The four higher values, from 1 to 2 francs, show the intricate details which

make an engraved stamp the art work it usually is. Note especially the details

in the clothing on the 1 franc value, the lace collar on the 1f20 value and the

curly wig on the 1f50 value. These middle value definitives, now also

known as the Historical Series, were issued in 1941.

The ideologies of Karl Bickel’s Paxmal have been reflected in his stamp work as well. The 1939 National Exhibition Zurich set is a prime example of this with both central ideas of Bickel’s philosophy represented: physical activity symbolised by handcrafted products on the 10 cents value and spiritual activity symbolised by Swiss culture on the 20 cents value.

The Swiss ‘Peace’ set from 1945 includes three values engraved by Karl Bickel. Again, we find imagery from Bickel’s Paxmal monument on the stamps, not least because of the inclusion of the word PAX which is also proudly displayed on the front of Bickel’s monument. The 10 francs value portrays the central mosaic of the Paxmal monument: an elderly couple, looking back contented at their fulfilled lives. The woman’s hands, resting peacefully in her lap, are depicted on the 5 francs stamp. Together with his first engraved Pestalozzi stamp, this was one of Bickel’s favourites.

The ideologies of Karl Bickel’s Paxmal have been reflected in his stamp work as well. The 1939 National Exhibition Zurich set is a prime example of this with both central ideas of Bickel’s philosophy represented: physical activity symbolised by handcrafted products on the 10 cents value and spiritual activity symbolised by Swiss culture on the 20 cents value.

The Swiss ‘Peace’ set from 1945 includes three values engraved by Karl Bickel. Again, we find imagery from Bickel’s Paxmal monument on the stamps, not least because of the inclusion of the word PAX which is also proudly displayed on the front of Bickel’s monument. The 10 francs value portrays the central mosaic of the Paxmal monument: an elderly couple, looking back contented at their fulfilled lives. The woman’s hands, resting peacefully in her lap, are depicted on the 5 francs stamp. Together with his first engraved Pestalozzi stamp, this was one of Bickel’s favourites.

As

with the definitive set, Bickel’s proofs show how he experimented with the

various images. Most striking among these is a die proof of the 10f value which

has the portrait of the lady on her own. However, the couple together conveyed

Bickel’s message much more poignantly, as does the 5f stamp with the folded

hands, so it is clear why Bickel eventually made the design choices he did.

In 1949, Bickel’s second large definitive series for

Switzerland was issued, entitled ‘Technology and Landscape’. The origins for

this set may be traced back to the year 1942, when Karl Bickel won a

competition for future stamp designs. He had submitted an essay which was very

much like the eventual 20c value depicting Grimsel reservoir. From that design

sprung the idea to create a definitive series based once again on Switzerland’s

natural beauty, but now focusing more on mankind’s ‘modification’ of it, thereby

promoting Switzerland’s economic expertise rather than touristic beauty.

Before

settling on the theme of technology in the landscape, though, Karl Bickel toyed

with the idea of depicting people at work in their natural environments. A

number of die essays exist exploring this theme, but they were rejected in

favour of a more traditional landscape series, with technology included.

In preparation of this series, the Swiss PTT bought a new printing press in

1945; the SSR II, this time made by WIFAG in Switzerland. And again, seeing he

was to create the new definitives as well, Karl Bickel engraved the trial

stamps to be used for test runs for the new definitive set, in the ‘Cross and

Ball’ design.

Karl Bickel made a large number of die essays, some of which were eventually not adopted for the series. One of those is an engraving of a bird’s eye view of an airport, with another design showing a railway carriage moving up a mountain slope.

But we mainly find die essays of designs which have only been tweaked a little until the final design solutions were met with. Particular to these die proofs is the fact that the denominations often changed as well.

Karl Bickel made a large number of die essays, some of which were eventually not adopted for the series. One of those is an engraving of a bird’s eye view of an airport, with another design showing a railway carriage moving up a mountain slope.

But we mainly find die essays of designs which have only been tweaked a little until the final design solutions were met with. Particular to these die proofs is the fact that the denominations often changed as well.

The 20 cents of the set, depicting the Grimsel reservoir, had to be re-engraved

quite soon after introduction of the stamp because the engraving wasn’t deep

enough and therefore the printing plate wouldn’t last long enough. Only 900,000

stamps had been printed so far. This led to two distinct types, which can be

distinguished by the number of lines in the water above the rounded rock; Type

I has three lines, Type II has only two lines. Furthermore, the cross-hatching

above and to the right of the figures 20 is stronger and extends further up on Type

II. There is a subtype of Type II, on which the cross-hatching does not really

extend above the 2 of 20. This type is found on coil stamps only.

The Swiss PTT was so proud of Bickel’s work that it produced

a presentation booklet for high-ranked and foreign guests which included the

whole new definitive set, alongside the previous definitive stamps for the

middle and higher values. The booklet was the perfect showcase for Karl

Bickel’s talents. It also included a private engraving by Bickel of a Swiss

mountain range.

In 1960, Bickel’s Technology and Landscape definitives were replaced by a new set which depicted either postmen or buildings. Whilst Bickel had no involvement with this set, he did submit a number of engravings for the high values of that set, for which the design remit was to symbolise either humanitarianism, christianity or democracy. Bickel’s essays depicted ideas such as tranquillity, peace and inner reflection. This work was very much like his many oil paintings, so once again we find that Bickel’s private art is mirrored in his stamp work. However, the Swiss PTT did not adopt his work and in the end opted for a more traditional and obvious design solution, by issuing the four ‘evangelists’ stamps in 1961.

Karl Bickel was huge admirer of the work of Swiss painter Albert Ankers. Ankers used to portray ordinary Swiss life in the nineteenth century, in all its rural and alpine glory. His portraits were enduringly popular and earned him the nickname of National Painter of Switzerland. In 1952 and 1953 Bickel chose two of Anker’s portraits, a boy and a girl, as the subjects of the annual Pro Juventute series.

In 1960, Bickel’s Technology and Landscape definitives were replaced by a new set which depicted either postmen or buildings. Whilst Bickel had no involvement with this set, he did submit a number of engravings for the high values of that set, for which the design remit was to symbolise either humanitarianism, christianity or democracy. Bickel’s essays depicted ideas such as tranquillity, peace and inner reflection. This work was very much like his many oil paintings, so once again we find that Bickel’s private art is mirrored in his stamp work. However, the Swiss PTT did not adopt his work and in the end opted for a more traditional and obvious design solution, by issuing the four ‘evangelists’ stamps in 1961.

Karl Bickel was huge admirer of the work of Swiss painter Albert Ankers. Ankers used to portray ordinary Swiss life in the nineteenth century, in all its rural and alpine glory. His portraits were enduringly popular and earned him the nickname of National Painter of Switzerland. In 1952 and 1953 Bickel chose two of Anker’s portraits, a boy and a girl, as the subjects of the annual Pro Juventute series.

When Bickel’s work for the annual Pro Juventute series was finally coming to an

end, he rounded his oeuvre off with yet more portraits by the Swiss painter

Albert Ankers. Again, the portraits of a boy and a girl were chosen for

Bickel’s final two Pro Juventute stamps, issued in 1963 and 1964.

Bickels’ rendition of the Anker portraits proved of long

lasting popularity. As late as 1986, when Karl Bickel had not engraved a single

stamp for well over two decades and had already passed away, the Swiss PTT

produced special sheetlets to mark the birth centenary of the engraver. The

sheetlets all included Anker’s portrait of a girl, engraved by Bickel for the

1964 Pro Juventute series, cancelled by various special postmarks of places

which had special significance to Karl Bickel’s life.

When, in 1962, a special Pro Juventute set was issued, to

mark the fiftieth anniversary of the series, the decision was made to not have

it include a Bickel portrait. This seems rather odd for the series had become

hugely popular because of Bickel’s portraits and Bickel had become hugely

popular because of his Pro Juventute portraits.

Instead,

Bickel was given the opportunity to engrave his first portrait for that other

Swiss annual charity set: the Pro Patria series. He would engrave portraits for

three of those sets, issued in 1962, 1963 and 1964.

Although Karl Bickel would mainly engrave stamps for Switzerland, he did do the

odd engraving for other countries as well, such as Liechtenstein. In 1945,

Bickel engraved the two highest values of the Troyer definitives, named after

its designer, consisting of a 5 francs Arms design, which would be issued in

two colours, and a 10 francs stamp depicting a statue of St. Lucius,

Liechtenstein’s patron saint. The actual statue itself was one of Bickel’s

favourite statues. The 10 francs stamp was issued in sheetlets of four

surrounded by a frame of lettering which included a credit for the engraving by

Karl Bickel.

In

1950, Karl Bickel would engrave yet another stamp for Liechtenstein. This time

it was the ‘Crown on a background of diamonds’ design for the country’s

Official stamps. Although the various catalogues do not credit Bickel for the

engraving, once again the sheet margins of the issue do.

Bickel’s favourite non-Swiss stamp was the engraving he did for the 1954

Liechtenstein ‘Termination of Marian Year’ issue. He is said to have been very

pleased with the way he managed to translate the twelfth-century wood carving

into a fine engraving.

In 1946, Karl Bickel got the chance to engrave a set for Portugal which was

being produced in Switzerland by the printers Courvoisier. It consisted

of a set of eight stamps showing various Portuguese castles. One of the values

would also be issued in a miniature sheet of four, printed in a different

colour.

In 1948, Karl Bickel engraved his first work for Luxembourg, printed by the Swiss printers Courvoisier. It is a definitive set portraying the Grand Duchess Charlotte, which would remain in circulation for over a decade. Bickel’s portrait of the Grand Duchess of Luxembourg was also used for a 1956 Luxembourg set of two stamps marking the centenary of the Council of State.

Karl Bickel’s son, Karl Albrecht Bickel, also known as Karl Bickel Junior, was also a gifted engraver. Growing up as an only child tucked away in the mountains, with an artistic father constantly at his side, it was almost inevitable for the young boy to become an artist as well. Karl Bickel Senior taught his son the art of engraving and passed on his love for stamps. This resulted in some fine teamwork on stamps before Karl Bickel Jr started his own career as a stamp engraver.

In 1948, Karl Bickel engraved his first work for Luxembourg, printed by the Swiss printers Courvoisier. It is a definitive set portraying the Grand Duchess Charlotte, which would remain in circulation for over a decade. Bickel’s portrait of the Grand Duchess of Luxembourg was also used for a 1956 Luxembourg set of two stamps marking the centenary of the Council of State.

Karl Bickel’s son, Karl Albrecht Bickel, also known as Karl Bickel Junior, was also a gifted engraver. Growing up as an only child tucked away in the mountains, with an artistic father constantly at his side, it was almost inevitable for the young boy to become an artist as well. Karl Bickel Senior taught his son the art of engraving and passed on his love for stamps. This resulted in some fine teamwork on stamps before Karl Bickel Jr started his own career as a stamp engraver.

The problem with this teamwork is that it has not always

been officially notified as such and catalogues or even official records do not

always mention the fact. But I have had the opportunity to interview the widow

of Karl Bickel Jr, Mrs Verena Bickel-Courtin, and she was able to shed some

more light on the work done by father and son.

Not officially credited but already more or less generally known to be engraved by the son was the 1956 Pro Juventute stamp portraying Carlo Maderno. The engraving style showcased is a little bolder from what one had become used to when looking at the father’s work. Mrs Bickel-Courtin has confirmed the whole stamp was engraved by her late husband.

In 1964, Liechtenstein issued a single stamp commemorating the death centenary of the historian Peter Kaiser. Both design and engraving are officially attributed to Karl Bickel Sr. However, a chance find of a First Day Cover threw some first doubts on this claim. The cover was signed by Karl Bickel, but stated ‘K Bickel sen / & Sohn’. Looking at the whole sheet, we yet again find the design and engraving attributed to ‘Karl Bickel sen’. A possible explanation was that the cover had been engraved by the son, rather than (parts of) the stamp. But another chance find, this time of an autographed sheet, caused more doubt. This sheet, too, was signed ‘K Bickel sen. & Sohn’, which made it extremely likely that Karl Bickel Jr had also worked as an engraver on this particular stamp. Again, Mrs Bickel–Courtin confirmed that the whole stamp had been engraved by her late husband, with Karl Bickel Sr providing the design.

Not officially credited but already more or less generally known to be engraved by the son was the 1956 Pro Juventute stamp portraying Carlo Maderno. The engraving style showcased is a little bolder from what one had become used to when looking at the father’s work. Mrs Bickel-Courtin has confirmed the whole stamp was engraved by her late husband.

In 1964, Liechtenstein issued a single stamp commemorating the death centenary of the historian Peter Kaiser. Both design and engraving are officially attributed to Karl Bickel Sr. However, a chance find of a First Day Cover threw some first doubts on this claim. The cover was signed by Karl Bickel, but stated ‘K Bickel sen / & Sohn’. Looking at the whole sheet, we yet again find the design and engraving attributed to ‘Karl Bickel sen’. A possible explanation was that the cover had been engraved by the son, rather than (parts of) the stamp. But another chance find, this time of an autographed sheet, caused more doubt. This sheet, too, was signed ‘K Bickel sen. & Sohn’, which made it extremely likely that Karl Bickel Jr had also worked as an engraver on this particular stamp. Again, Mrs Bickel–Courtin confirmed that the whole stamp had been engraved by her late husband, with Karl Bickel Sr providing the design.

The

final collaboration of father and son was the 1965 engraving of Madonna for

Liechtenstein. This time, no doubt over the collaboration could ever exist, for

both father and son are credited in the sheet margins. According to Mrs.

Bickel-Courtin, Bickel Sr engraved the Madonna, with Bickel Jr engraving the

intricate background. This would also be Karl Bickel Sr’s final stamp engraving.

In an interview Bickel once said that artists live a

semi-normal life without haste. Even in old age they remain mentally alert. He

certainly lived up to that remark, for it was not until he reached the age of

79 that he finally lay down his burin. His retirement as stamp engraver, and

his eightieth birthday in 1966, would initiate a number of national

retrospective expositions of his work. The PTT Museum in Bern honoured Bickel’s

work particularly in an exposition of its stamp engravers, and the Museum of

Applied Arts in Winterthur held an exposition of Bickel’s work alone.

Bickel would remain active as an artist and even though his

relevance in the artistic world would diminish a little, he was still the

recipient of many honours. In 1966, Bickel received the Culture Prize and in

1967 he was named honorary citizen of Walenstadtberg. On that occasion, many

high-placed visitors made the trip to Bickel’s home in the mountains, including

Liechtenstein royalty and the complete Swiss government.

On

November 6, 1982, Karl Bickel passed away peacefully at home in his beloved

Walenstadtberg mountains. In his honour, Karl Bickel Jr engraved his father’s

portrait which was used as promotional material for the national philatelic

exhibition NABA Züri 84.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Gaudard, H.

E., Die Bilder zu den Frankomarken der Ausgaben 1936-1941. Bern

1943.

Gaudard, H.

E., Die edle Kunst des Stahlstechens. Bern 1965.

Gibbons Stamp

Monthly, September 1969.

Schunk, V. and Diggelmann, W., Karl

Bickel. Zürich 1986.

(The original version of) This article was first published in Gibbons Stamp Monthly of March and April 2016 and is reproduced with their kind permission.

You will find Karl Bickel's database HERE.

(The original version of) This article was first published in Gibbons Stamp Monthly of March and April 2016 and is reproduced with their kind permission.

You will find Karl Bickel's database HERE.